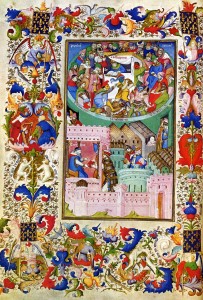

The last fortnight has been spent trying to get to grips with how Scottish kingship differs from the English style of monarchy in order to understand its representation in Ane Satyre. This is not just for the production but to go towards a paper being delivered on the panel ‘Sexuality and Sovereignty in the Early Modern Drama’ at the Shakespeare Association of America conference next year.

Political differences between the England and Scotland came to the forefront after the Union of the Crowns in 1603, when James was roundly criticised for using Scottish methods in the English parliament and at court, as Jenny Wormald has incisively examined in her essay, ‘James VI and I: Two Kings or One?’. She reinforces the notion that there was less constitutional sophistication in Scotland writing that, “this less developed government did less governing” (1983, p193). In line with arguments made by Roger Mason she claims that when Scottish political philosophy did develop during the sixteenth century, it was due to “the appearance of professional lay lawyer-administrators, [a] product of over a century of growing lay literacy, [which] substantially widened interest in central government beyond the circle of literate clerics” (1983, p194). Yet she denies that the lack of legalistic underpinning of theories of Scottish government prior to this led to it being ineffective. To the contrary, in Scotland stuff gets done, and often more quickly than in England, just in a different way.

The way in which laws are passed and rapprochement between political parties is attained in Scotland can seem fairly radical, however the methods do not in fact detract from the “patriotic conservatism” that Mason contends was the predominant feature of late medieval Scotland’s political ethos (1987, p146). Decisions were reached through debate and argument rather than precedent and law, meaning that parliamentary processes were active, lively and reciprocal. Nevertheless Wormald says that such political events as the argument between James VI and I and Anthony Melville in 1596 are frequently misinterpreted as a sign of backwardness and impropriety: “The point of that debate, in which Andrew Meville seized the king’s sleeve, calling him ‘God’s silly vassal’, is entirely lost if it is seen to exemplify the lack of respect with which Scotsmen supposedly treated their kings” (1983, p197). The Scottish system rather existed in stark contrast to the hierarchical and, since Henry VIII and the Reformation, increasingly absolutist monarchy of England. While some of the addresses made to power in Ane Satyre of the Thrie Estaitis may seem surprising to readers of early English drama therefore, they should in fact be interpreted in light of a Scottish political philosophy which did not view dissension, and even outright hostility, as unpatriotic.

References:

Roger Mason, ‘Kingship, Tyrannt and the Right to Resist in Fifteenth Century Scotland’, The Scottish Historical Review 66, No. 182, Part 2 (1987) pp.121-151

Jenny Wormald, ‘James VI and I: Two Kings or One’, History 68 (1983) pp.187-209