I was absolutely honoured to interview the original Sandy Solace from Tyrone Guthrieâs famous 1948 production of A Satire of The Three Estates the other day. A true moment of oral history that speaks for itself, and does so in a âricht merry voiceâ. Jamie Stuart, what a character.

Jamie Stuart, the original Sandy Solace, on Tyrone Guthrie’s production

Jamie Reid-Baxter on ‘A Satire of the Three Estates’

Jamie Reid-Baxter, the early theatre and Scottish literature expert, discusses his previous experience of working on productions of A Satire of the Three Estates, focusing on his part of Folly, a character who was cut out of the famous Edinburgh University productions. Jamie says that that this was wholly wrong, as he serves as the âmirror image of Diligence in the playâ suggesting that âboth Diligence and Folly are David Lindsayâs alter egosâ.

Jamie speaks about his excitement at a full, unedited version being performed in June, particularly the political urgency of the piece that will be revealed as a result. He also discusses the âfundamentalâ place Lindsay holds in the Scottish canon, in that his work looks both backwards and forwards. As a former translator at the European Parliament, Jamie helpfully discusses the dramatic appeal of the Middle Scots tongue, talking about the âroughness of Scots, the Germanic side of Scots, what you call in France the terrien, the clods of earth, the earthiness of it⦠but also the grandeur of those harsher consonants and pure vowel soundsâ. Reid-Baxter finishes by putting Lindsay in the literary tradition of William Dunbar, Gavin Douglas, Alexander Scott and Alexander Montgomerie, saying his work can âshed light right across the canonâ, but is also innovative, discussing how Lindsay extends the Scottish tradition of flyting in this play.

Was the 1540 Interlude authored by David Lindsay?

Before further posts detailing our discussions about the staging of the outdoor version of the Satire in June, here is another essay from Greg Walker about the feasibility of the Interlude that was performed before James V on Epiphany in 1540 being an earlier version of the Lindsay’s play and authored by him.

The relationship between the ‘lost’ interlude played in Linlithgow in 1540 (which is accessible only through the ‘notes’ and description sent to Thomas Cromwell by the English agent William Eure), and the full version of The Thrie Estaitis (which I will refer to here as the Satire), for which we have two surviving texts, has always been a matter for debate among scholars. Lyndsay’s first editor of the modern era, Douglas Hamer, argued in the 1930s that the 1540 Interlude was an earlier version of the Satire (Hamer, Works, II, pp. 1-6), but critics have not always agreed. Angus Calder thought the Interlude ‘had one or two features in common with the Satire’ (‘Introduction’ to Spence, p. vii), John MacQueen that the 1540 interlude ‘was only generally similar to the…[text] which has survived’ (p.135). Perhaps most powerfully, R.J. Lyall, while acknowledging that ‘the affinities between the interlude and The Thrie Estaitis are striking enough for the former to be widely accepted as the original version of the latter’, was nonetheless troubled by the ‘many differences’ he also saw between the two, and so on balance concluded with cautious pessimism about our ability to connect them.

William Eure’s letter and the ‘nootes of the interluyde’ mentioned by Greg can be found in the Documents section of the website incidentally –

Director, Gregory Thompson, on the revealing process of rehearsing A Satire of the Three Estates

Gregory Thompson, director of the productions this June, talks about his experience of working on the text for the first time and his realisation of the truly political nature of the play, saying that he recognised that this was as much a âparty political broadcastâ as an entertainment.

The challenges of the play, according to Gregory, are its historic distance from us as well as the changing nature of theatre over time â now we see plays almost entirely as entertainment. The other major difference is the playâs staging which is so remote from modern techniques. Moreover, the shadow of Shakespeare looms large over sixteenth-century theatre in general, so zoning in on the peculiarly Scottish, as well as the pre-Shakespearean character of this play, will present a challenge.

Gregory also discusses the Interlude of 1540 â its separateness and its connectedness to the Satire. Many of the entertaining digressions from the hard politics of the Satire are missing, giving the Interlude a sense of a being a âdramatized green paperâ. This could, of course, result from the fact that the only source we have for the Interlude, a letter from William Eure to Thomas Cromwell, necessarily emphasises the aspects of the drama that would have been interesting to the English Kingâs chief minister. Greg Walker has recently written about the differences between the two texts of the Satire and the Interlude and his paper will be uploaded to the website very soon.

Gerry Mulgrew reads Folly’s sermon… and a diary of the rehearsal period

For those of you interested in the sorts of discussions that occurred during the rehearsal period with Alison Peebles, Tam Dean Burn, Gerry Mulgrew and Gregory Thompson, today you’ll be able to find a diary in the documents section which reveals our preoccupations during that week in January. Please do have a look and offer suggestions for any of the unanswered questions the readings provoked, the key ones being:

1. What are the differences between the 1540 and 1552/4 pieces, and between the Satire and other drama of the period?

2. What is the role of Diligence?

3. To modernise or not to modernise?

Here, also, is a video of Gerry Mulgrew reading out Folly’s sermon at the very end of the play. As it says at the beginning of the rehearsal diary, this is where we started, because Gregory Thompson found it very strange that such an episode should happen after the seeming climax of the play – the enactment of the laws discussed by the parliament. Yet Folly comes on and undermines this apparently ‘serious’ conclusion by delivering a speech which states ‘Stultorum numerus infinitus’ - the number of fools is infinite. His monologue takes the form of a sermon joyeux, a mock-sermon delivered by someone who is not a preacher. In it, he distributes a number of folly hats to society’s fools and his targets are merchants, old men who marry young girls, the clergy, and kings. The section on kings moves his sermon from the general to the specific as he laments Scotland’s foreign policy and discusses current European conflicts. He ends by invoking the souls of two contemporary court fools, Gilly‑mouband and ‘good Cacaphaty’, continuing to locate his words in the Scottish present. The whole speech destabilises any tidy conclusion to the play by shifting responsibility back to the royal spectators and the audience themselves.

The image at the top of the page, incidentally, is Holbein’s depiction of a fool’s sermon to an audience of fools from Erasmus’ In Praise of Folly.

Gerry Mulgrew on A Satire of the Three Estates

Another treat from the recent script work undertaken with Scottish actors – this time an interview with legendary actor and theatre director, Gerry Mulgrew. Having served as Artistic Director of touring theatre company Communicado for the last 30 years, if anyone can talk about the significance of the Satire for Scottish theatre history, it’s Gerry.

Of particular interest is his claim that the very local and seemingly historically specific concerns of the play in fact become “timeless and universal” because they concern the poor, social reform, and the corruption of the state – issues which still affect us today. He says that his prior belief that the play was “stuffy” was challenged by the rehearsal process, and that the actors “have been rather impressed and surprised by how modern some of the ideas seem to be for the middle of the sixteenth century. It is a great, passionate, humanist piece.” Like Tam, Gerry picks up on the language of the play; both actors found Robert Burn’s poetry a useful gateway for undertanding it, although Gerry sees it as more of a challenge in terms of its orthography and rhythms. But he also celebrates its uniqueness and its richness which he says produces a Scottish voice that is “glorious”.

Enjoy.

Tam Dean Burn on A Satire of the Three Estates

We hit the ground running in 2013 with a series of production meetings at Stirling Castle followed by nine days of intensive script work with actors Alison Peebles, Gerry Mulgrew, Peter Kenny and Tam Dean Burn. It was the first time we had really tackled the play in its full, rich, and complex entirety… more of which later.

In the meantime, here’s TV and film actor Tam Dean Burn talking stirringly about his experience of working on the text, with academics, and his thoughts on the Satire‘s themes and language. (The above image is the view he mentions; the panorama of Arthur’s Seat and the Salisbury Crags from Greg Walker’s office window!)

Who is John the Commonwealth?

A central question the project will need to address in the New Year is the costuming and appearance of Satyre‘s characters. Chief among these will be John the Commonwealth, and to do so, the team will first have to decide who, or even what, he is. Information in the play is hardly indicative. He bursts on to the stage much like the Pauper – “Out of my gate, for God’s sake let me ga!” (2422) – and yet does not suffer the abuse that Pauper does on the basis of his physical presentation, who is subjected to a litany of name-calling such as “False whoreson raggit carl” and told to leave “the field” (1946, 1939). So is John not “raggit” then? How does he demonstrate the necessary authority for Diligence to immediately smooth his path towards conference with the king (2434)? A significant sartorial transformation occurs when his suggested reforms are passed by Parliament at the end of the play and he is absorbed into them – “Here shall they clothe John the Commonweal gorgeously, and set him down amang them in the Parliament” (3802 s.d.). John now wears a “gay garmoon” but what did he wear before?

Jean E. Howard and Paul Strohm argue that John is the “indigenous voice of reform” in Ane Satyre and that both he and Pauper are “imagined from within, as internally self-regenerating forces”. Does this direct us towards some sort of native tradition of Scotland – tartan, kilts. etc – or perhaps even a connection with nature? John himself says that the commonwealth “want[s] clais” (2445). As it’s embodiment, does John too? Perhaps he occupies a similar position to the wild man of prose romance on the border between society and the wilderness, his liminal energy informing his ability to tell truth to power.

As a representation of the ‘commonwealth’, Carol Edington has argued against situating John in terms of class, rank or occupation, writing:

As much psychological and political, the ideal of the commonweal conveyed very real feelings of organic unity, physical dynamism, and a very emotive patriotism, Nowhere is this more vividly conveyed than in Lindsay’s dramatization of John the Commonweal. It should perhaps be stressed at this point that the character of John, despite his often hungry and ragged appearance, was not a symbolic representation of “the poor” or even, more specifically, of the rural poor. When Lindsay required such a figure he introduced the Pauper or the traditional “John Upland”. John the Commonweal on the other hand represents the universal and public good of the entire community and not the interests of any single element. He is the dramatic embodiment of a principle, not a party, an ideal and not an individual. (p120, my itals)

It is certainly true that if John is clothed as a member of the Scottish citizenry then this will have a knock-on effect in terms of all of the represented social relationships in the play, something we should be very wary of. But, for John to be “not an individual” is fine in theory, however theatre requires the practical expression of such interpretations. If John embodies a principle then how can that principle in turn be embodied? When the team gather at Stirling Castle early in 2013 to begin fixing aspects of the performance, such questions are sure to be hotly debated.

References:

Carol Edington, Court and Culture in Renaissance Scotland: Sir David Lindsay of the Mount, University of Massachusetts Press, 1994

Jean E. Howard and Paul Strohm, The Imaginary “Commons”, Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies, 37.3, 2007

Drama and Reforming Ideals in the 1530s

Whether David Lindsay can accurately be described as a Reformer or not seems to be a matter of some contention for critics and historians. For Joanne Kantrowitz, Lindsay is a Reformer, while Carol Edington errs on the side of caution when assessing his position, noting Lindsay’s connection to Reformers at the court but falling short of numbering him among them. For Edington, Lindsay is a reformer with a small ‘r’, outraged by clerical abuses and yet steering clear of doctrinal matters in his literary works.

What has struck me as interesting in my reading today is how Lindsay manages to criticise the Catholic clergy in 1540 in a way which enabled James V to exhort the Bishop of Glasgow to “reform their factions and manners of living”, when other playwrights of the 1530s were punished for the same thing. In his section on ‘Performances and Plays’ in The Edinburgh History of Scottish Literature, Volume One (2007), Bill Findlay relays that:

In 1535, John Kyllour, a Dominican friar, wrote a Historye of Christis Passioun, performed in the Castlehill playfield, Stirling, before James V, his court, and the townspeople. Kyllour employed the format of the passion play to criticise bishops and priests; for this, after a period as a hunted man, he was burned at the stake in 1539. James Wedderburn of Dundee wrote, and had performed there about 1540, plays which satirised the Roman Catholic clergy: a ‘tragedie’, Beheading of Johne the Baptist, and a ‘comedie’, Historie of Dyonisius the Tyranne. For these, he had to flee into exile in France. (p255-6)

How is it that Lindsay is not only able to attack the clergy, but has his play used as springboard for James to do the same, while contemporary dramatists suffer exile and execution for doing so? Sadly, because neither Kyllour or Wedderburn’s texts survive, we will never be able to assess the qualitative differences between the forms and extent of reformation they advocate and how these differ from those that might have been suggested by Lindsay, if, indeed, Lindsay’s critique in the non-extent Interlude of 1540 bore any relation to that found in the Satyre of the 1550s. It does seem astonishing that Lindsay’s attack on prelates and the “naughtiness in Religion” should have been sustained and vehement enough to justify James V’s response, while Kyllour and Wedderburn suffered such a fearful fate for their reforming ideals.

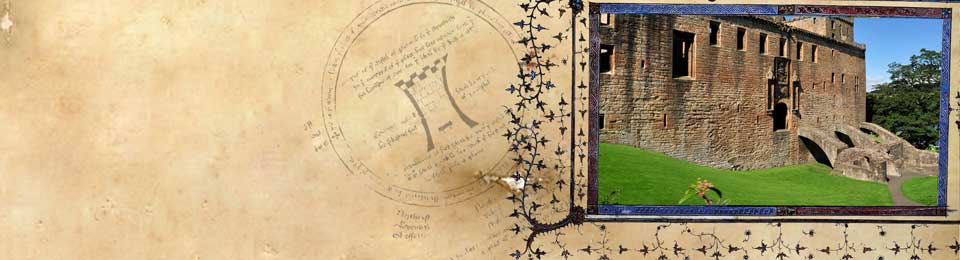

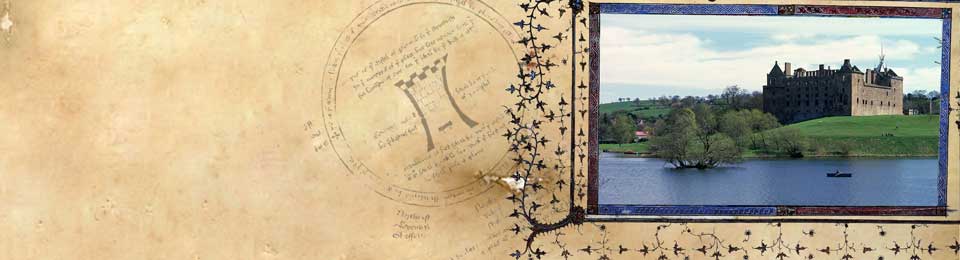

Staging and Representing the Scottish Renaissance Court…begins.

Welcome to the blog for Staging and Representing the Scottish Renaissance Court, a major two year project which will explore Stuart drama, politics and place during the mid-sixteenth century through the staging of David Lyndsay’s A Satire of the Three Estates at Linlithgow Palace and Stirling Castle in 2013. Staging the Scottish Court is a collaborative, interdisciplinary project drawing on performance, film, literary and historical analysis, archaeology and architectural studies. It brings together Edinburgh, Glasgow, Lincoln, Oxford Brookes and Southampton Universities, with Historic Scotland, theatre professionals and film-makers.

This blog will chart the research process over the course of the project; firstly as we approach the full outdoor production of the Satire at Linlithgow Palace, as well as indoor versions of Lyndsay’s non-extant 1540 Interlude as reconstructed by the research team in the shell of the Great Hall At Linlithgow, and the actual Great Hall of Stirling Castle. Following the performances of June 2013, this blog will enable a continuation of the debates instigated by the project. It will also link up with a website which will host professional films of these unique theatrical events as well as other research and educational materials.

The project aims to address a number of questions which fall into three broad categories; literary, textual and performance analysis of Sir David Lyndsay’s Ane Satyre of the Thrie Estaitis (A Satire of the Three Estates); archival and iconographic analysis of Scottish Renaissance court culture at Linlithgow and Stirling; and contemporary understanding of ‘public history’ with specific reference to importance of historical truths and myths to Scottish nationalism.

- What was the nature of the dramatic interlude performed before James V at Linlithgow, and what was its relationship to the later performances of 1552 and 1554?

- In what ways is Scottish Renaissance court culture reflected in Ane Satyre and in the related physical evidence of Renaissance architectural features of the Stuart royal palaces such as the Stirling Heads?

- In what ways do performances and media re-workings of historical events shape contemporary national, political and popular understandings of the past?

The project will run parallel to a crucial period in Scottish history. Just as Lyndsay sought to investigate Scottish national identity and suggest reforms for his society in his epic play, Scotland once more finds itself at a crossroads as it heads towards the Independence Referendum in 2014. People are again asking what it means to be from Scotland. What elements of social and political organisation can be seen as distinctively Scottish? If Scotland is going to become an independent nation, what should it keep and what should it throw away? Independent or not, how should Scotland move forward into the future?

Such questions and more will be addressed on this page every fortnight or so. We hope you will check here, on the twitter account, and ultimately the project website, to see how research becomes performance, and how Scotland’s present interacts with the Scottish past at this critical juncture in its history.