Here’s the final blog post in the series of staging questions that the research team have been mulling over. This one concerns where characters may enter and exit from in our production.

Due to practicalities of performance the set has now been modified and, as it stands, the audience will still be enclosed within a ’round’ but the majority of the action will occur end-on. Here’s a sneak preview for you:

While the classical ‘in-the-round’ configuration with a central stage has been altered therefore, the form largely remains, and this raises issues of where the characters both enter and exit from. Do they come from behind the end-on stage – appearing before the audience – or are we still able to use the ‘field’ as an route to the stage – so that characters come through them? Below is the research team’s response to the director’s question: ‘Do the characters make their first entrance from the ‘field’. And Rex specifically – where does he enter from at the beginning of Part 1?’

Greg Walker – I think it matters where people come on from, as it indicates who and what level of society they are from. Those who come seemingly from out of the crowd, like John or Pauper, or the sowtar and tailor and their wives are reps of the people. Others clearly come TO the crowd and platea from outside – from outwith Scotland, whether villains like the Pardoner, or Flattery, or virtuous figures like Good Counsel, Verity, Correction, etc. Shouldn’t Rex emerge from out of his seat (as it were). He’s not from us – we don’t elect him or have a choice of who gets to be king. It’s decided for us by the powers that be.

Tom Betteridge â I think if characters come from outside Scotland they need to come through the field / audience â the only two places that people can enter are effectively from the field or from the court. As Diligence says when Pauper enters, âQuhair have wee gottin this gudly companyeoun? Swyith out of the field, – Pauper is a companion who has entered the world of the play from the field â but note that field is not a non-performing area â rather it is one that can be part of the âstageâ and at the same time it is the stageâs border or enabling frame. The characters who should not come from the field are, as Greg suggests, Rex but also the other courtly characters â I donât think Diligence should come from the field since, I would suggest, part of his weakness is that he lacks the authority implicitly given to those characters who can come from the field but transgress its limitations â i.e. Divine Correction and John the Commonwealth.

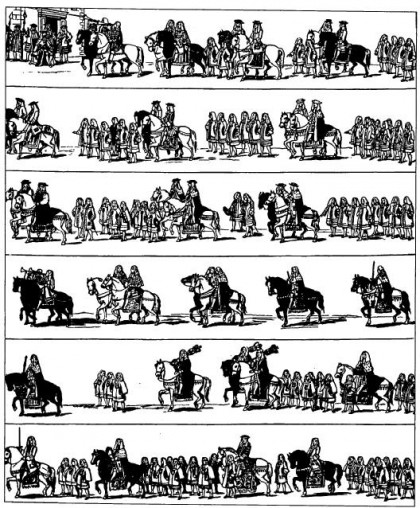

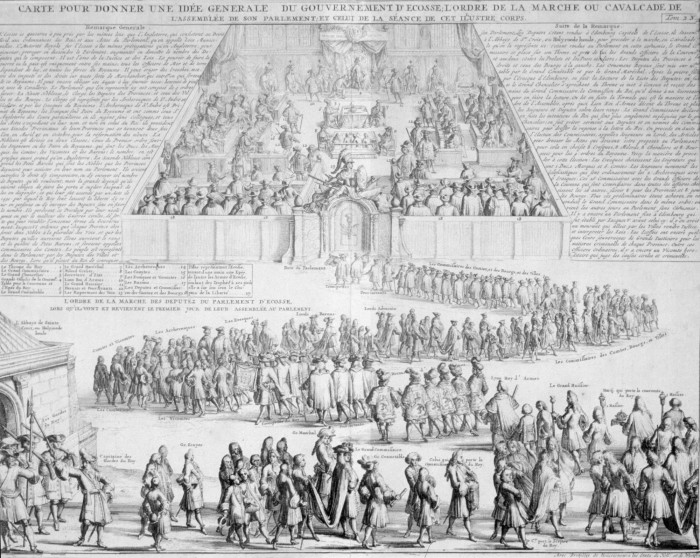

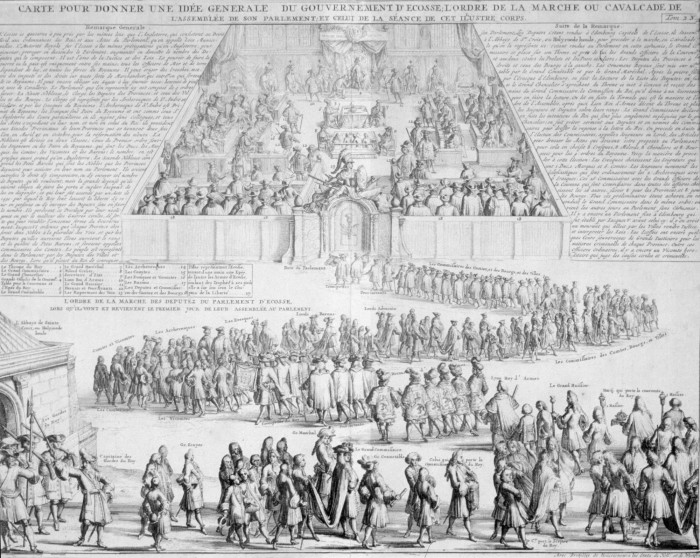

Ellie Rycroft â I agree with the above, especially that Rex shouldnât come through the field, but I think the fact that members ârideâ into parliament complicates things to an extent. I think thereâs something compelling about the display of the parliament during the riding â itâs as if they are saying âyou can see us, weâre off to do something important, but youâre not allowed to see whatâ, fully materialised when the Lyon King fences the space off. See images of parliamentary processions below.

John McGavin – I agree with the above. Some characters definitely do not come in through the audience. I do not see Diligence as coming through the audience: he can talk to them up close but he is a higher manâs functionary. Others definitely do. Some actions, however, are intended to be spectacular; they are public theatricality within theatre, and they constitute one of those elements of 16th century drama where the drama self-reflexively stages its own essential foundations â like the thematic use of disguise and impersonation or the moral staging of emblematic tableaux (such as the king and ladies lolling about in the first part described by Verity). This is an instance where the drama gives special force to the notion of watching: spectating becomes âwitnessingâ in the sense of bearing witness. Although Ellieâs image do not depict the crowd, we as lookers at the image are part of that crowd. Wherever the thrie estaitis come from (the palyeon) on their way to the parliament, their proximity to the people en passant is vital â they are coming backward âthrow this tounâ. James was later to âstageâ the nobles in a banquet at the Cross precisely so that the people could act as witnesses to it and so put the nobles under the pressure of public scrutiny and public memory. I would be inclined to start Part Two with Diligence announcing the thrie estaitis and getting the spectators to rise and take their hats off. The surprising entry from the pavilion of the backward estates would then be a shocking blow to the spectators who had been prepared to honour this event.

Sarah Carpenter â I suppose Iâd assumed that âcourtlyâ characters â king, three estates etc â come from the âpal3eounâ when they need to âenterâ. Thatâs formally stated for the three estates at the beginning of act 2, but I canât see where else the king would exit to (or therefore enter from). There are some characters who specifically seem to need to come from the audience, people like John the Commonwealth, the tradespeople, some of the vices. And they often are said to come âthrough the waterâ, which might suggest from the audience side of the platea? Although in fact some of them are said at times to âpas to the palyeounâ, like the Taylorâs wife at 1395. It seems important to be able to signify characters who come from âabroadâ as different from either of these groups. But they often establish this themselves through their entrance speeches, wherever they arrive from physically.