Early theatre expert, Peter Happé, has been generous enough to offer his response to our production of Ane Satyre of the Thrie Estaitis, somehow managing to condense five hours of staging and action into five pages. We’re incredibly grateful to Dr Happé for taking the time to reflect and report back on the performance.

Sir David Lyndsay, âA Satire of the Three Estates: Â Space â Language â Concepts

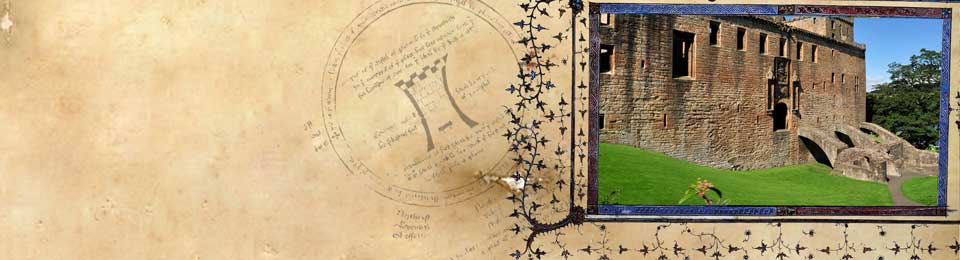

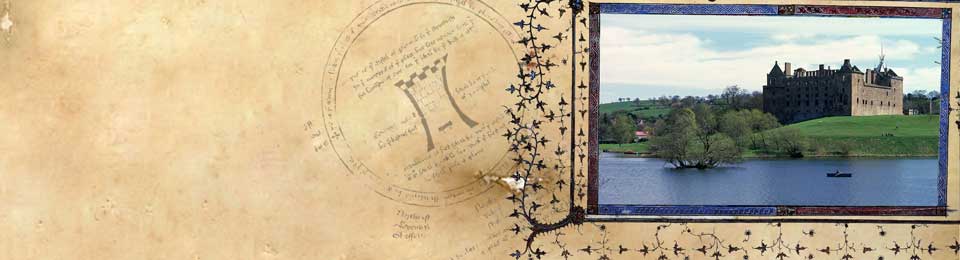

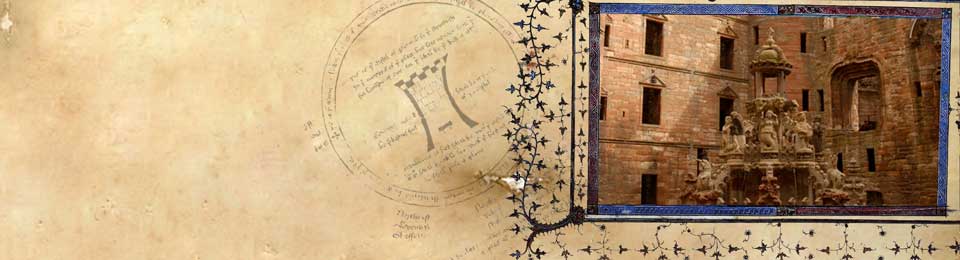

The layout of the acting areas for the original performances of Sir David Lyndsayâs Ane Satyre of the Thrie Estaitis in the sixteenth century is now difficult to discern though two of them were in the open air: at Cupar in Fife (1552) and the Greenside in Edinburgh (1554, in the presence of Mary of Guise, the Queen Regent). This meant that a shape had to be designed for the 2013 performance at Linlithgow. The presentation was set up on grass on a flat level with the castle, perhaps with a symbolic reference to the concept of royal authority, as a high, distant background. The acting area was an enclosed circle with four separate locations equidistant from one another on the circumference. Three of these were elevated circular stages and these were connected by an elevated walkway which formed a channel enabling the actors to pass freely between the fixed locations. This layout brought into play some very powerful dynamics regarding where the action took place and in the relationship between the audience and the action. The tallest of the four, nearest to the castle, had an upper level with stairs mounting to a throne and this construction, which had a hierarchical function, was the focal point of much of the action, especially for the  Parliament in Part Two. To one side of this the fixed location contained a large gallows with three nooses and three sets of stocks below: justice and punishment were clear implications. On the other side the location contained a separate throne, perhaps suggesting authority and contemplation. Although this circular outline may be perceived as owing something to the manuscript drawing for The Castle of Perseverance, and to the St Apollinaire painting by Fouquet, there is no doubt that that it was the result of some remarkably successful planning based upon a perception of possible effects.

Within the embracing circle the audience were admitted to sit on chairs (of their own) or on the grass.  A choice was made to keep the audience within the circumference and also to limit the amount of acting in this space at ground level: a notable decision in the face of much medieval evidence suggesting that a great deal of action often took place within such areas between fixed locations (the platea), especially in the Mystères for example. It had the effect of lifting much of the acting to the higher levels of the surrounding wall and the towers on it and it did bring the audience into close proximity to the action from time to time.  From within the circle the audience could see what happened at their own level, but for much of the time they were looking upwards to events taking place above them. Noticeably, and partly affected by the warm sunny weather, many of the audience settled the problem of observation by lying down and looking up at the action. But some effective moments did take place at ground level and several of the fools and vices had comic interaction with individuals in the audience, usually impertinent.   Â

One significant effect of this layout was that the audience was in polyvalent relationship to the action. They were both inside the action and outside it. There was a very large variety of areas of interest and there could be contrast and transition between them vertically and horizontally. Sometimes characters could speak across the divides between the acting areas and sometimes, especially in the fool episodes, there could be intimate relationships concentrated into a very small space. Unlike many modern outdoor presentations of medieval plays, audibility was excellent and this was no doubt a result of the decision to perform in an inward-looking enclosed space. A further resource in this layout was that some characters could be âparkedâ on the individual stages on the outside edge, while the action shifted to other areas and then they could be quickly brought to life again when required. This happened with the fools who spent long periods sitting in the stocks, and with Good Counsel who passed some time studying her New Testament. The facility was useful because the states of mind these characters represented remained as part of the audienceâs awareness even though dormant or peripheral. It is an effect perceivable in the original performances of medieval plays and it proved an effective resource here.

The physical features of the set gave rise to a number of powerful effects. The entry of thee three Estates in Part Two which the text requires to be made by their walking backwards led by their respective vices was particularly effective as they proceeded along the high walkways. When the Parliament was assembled on the main elevated area they formed a very impressive spectacle and made it apparent that many social levels of society were represented. The incursion by John the Commonwealth, a rather lonely figure was a telling contrast. The episodes concerning the vices were played in a variety of ways through the acting spaces. Apart from the occasions when they were in intimate contact with the audience they were also given a platform for engaging with one another, as when they were stocked and in the sequence which lead up to their final hanging. At this point the text gives a prompt for the crow which is to represent the soul of Falset and this was very skilfully managed

A great deal of music was incorporated into the performance. The musicians were in costume but interestingly for many of the instrumental episodes they were kept outside the circle and outside the limiting walls so that the music came into the performance almost invisibly. Instrumental music was used for setting up moods and for punctuation, but in several places the text of the play was set to music with the actors singing their lines. This feature may have been developed to give emphasis to certain episodes, especially when identifying characters near the beginning. It had a lively effect and for the most part did not obscure the words, though in some places words spoken by female actors were hard to discern because of the vigorous musical accompaniment. The original text gives some hints about the music and the enlarged effects on this occasion were of great benefit to the performance.

The text was performed in full and spoken in Scottish dialect. Perhaps at times it was a bit obscure and it did seem that there were some instances when only some of the audience were responding to what was being said. This might indicate that some people were more in tune with the appropriate pronunciation. However the language worked with remarkable effect and it was possible for the actors to convey the vigour of what they were speaking and to generate an awareness of the wit and versatility of Lyndsayâs text. It must be said that the quality of the acting and speaking was consistently outstanding. The performance revealed a range of rhetoric, whether it be the formal language of the Parliament, the preaching or the formal pronouncements of the king. But perhaps the most remarkable feature was the language given to the fools and vices which gave scope and opportunity using language like everyday speech. One notable feature was the success of the name-games played by the vices who made their names memorable to the audience by the ingenuity with which they distorted them. But this vigour was also to found in the language of John the Commonwealth as he exposed the unjust treatment he had received from the clergy. The Pauper had a great deal of success in his exploitation of Latin gerundives. Though in some respects he spoke as a common man he was given passages where the construction of his speeches was based on carefully arranged rhetorical features which made his case the more powerful and also provided the audience with an opportunity to appreciate Lyndsayâs verbal dexterity. It was striking that in the passages of dialogue set to music the language was also effective and persuasive.

The witty and rhetorical complexities of Lyndsayâs language and his capacity to treat his material critically reflect his concerns in writing the play and it is important to consider what impact the production had in terms of ideas. Whilst his own stance was civilised and discriminating and his satire revealed his longing for high moral standards, his picture of the society around him was a grim one. He does not let us see much that is joyful or contented and the range of his criticism is devastating in terms of all three estates. The most important objective was the abuses of the church and Lyndsay has compiled a comprehensive indictment of the abuses it perpetrated. His Protestant inclinations lead him to make much of the worldiness of the clergy and their defence of traditional privilege as against a perceived lack of true preaching.

But the church he portrays is embedded in a society controlled by a king and the production, by its layout and by the actions concentrated upon kingship, especially in Part One, showed how the crown was central and it brought out the importance of the instruction of the monarch towards a true perception of the responsibilities of his office. This was a theme which emerged even more strongly in the reconstructed Interlude and it is no doubt relevant to reflect that for a while Lyndsay was for a time a tutor to the young monarch.

However, the whole of society was involved as target for the satire and the play takes a dramatic turn towards the end in the introduction of the fools who bring out their own folly as well as that of those around them: Folieâs sermon pinpoints this. The distribution of hats to the king and to all involves everyone in the folly which is portrayed and the shape of the production with its emphatic inclusion of the audience within the physical limits of the play world made this plain. Lyndsayâs world is bleak one, his humour is raw and derogatory, and in this production we were made to see the enormity of the wrongs in society and the generality of responsibility for amending it from the king downwards. It was one of the achievements of this production that it made the audience feel the weight of such responsibility even though political and religious circumstances have changed greatly since the original versions were conceived.

Lyndsayâs exploitation of the grim comedy of folly in Part Two was made apparent in this production, especially in revelations of the gallows humour. But there is one further comment to be made about the presentation of the Acts of the Parliament. Theatrically there was a distinct change of mode here. The exceptional work of the trumpeter and the persistence of the actor reciting the acts could not hide the fact that Lyndsay was determined to make this a catalogue of abuses comprehensive. It was quite justified to retain all these details as witness to the severity of Lyndsayâs judgement upon the society around him. The dramatic pace slowed considerably during this recital but it was nevertheless valuable to have the intensity of Lyndsayâs satirical saeva indignatio fully revealed.

Peter Happé

University of Southampton

Bravo, Professor Huppe. A fine account of the fine performance.

Joanne Kantrowitz