For those of you interested in the sorts of discussions that occurred during the rehearsal period with Alison Peebles, Tam Dean Burn, Gerry Mulgrew and Gregory Thompson, today you’ll be able to find a diary in the documents section which reveals our preoccupations during that week in January. Please do have a look and offer suggestions for any of the unanswered questions the readings provoked, the key ones being:

1. What are the differences between the 1540 and 1552/4 pieces, and between the Satire and other drama of the period?

2. What is the role of Diligence?

3. To modernise or not to modernise?

Here, also, is a video of Gerry Mulgrew reading out Folly’s sermon at the very end of the play. As it says at the beginning of the rehearsal diary, this is where we started, because Gregory Thompson found it very strange that such an episode should happen after the seeming climax of the play – the enactment of the laws discussed by the parliament. Yet Folly comes on and undermines this apparently ‘serious’ conclusion by delivering a speech which states ‘Stultorum numerus infinitus’ - the number of fools is infinite. His monologue takes the form of a sermon joyeux, a mock-sermon delivered by someone who is not a preacher. In it, he distributes a number of folly hats to society’s fools and his targets are merchants, old men who marry young girls, the clergy, and kings. The section on kings moves his sermon from the general to the specific as he laments Scotland’s foreign policy and discusses current European conflicts. He ends by invoking the souls of two contemporary court fools, Gilly‑mouband and ‘good Cacaphaty’, continuing to locate his words in the Scottish present. The whole speech destabilises any tidy conclusion to the play by shifting responsibility back to the royal spectators and the audience themselves.

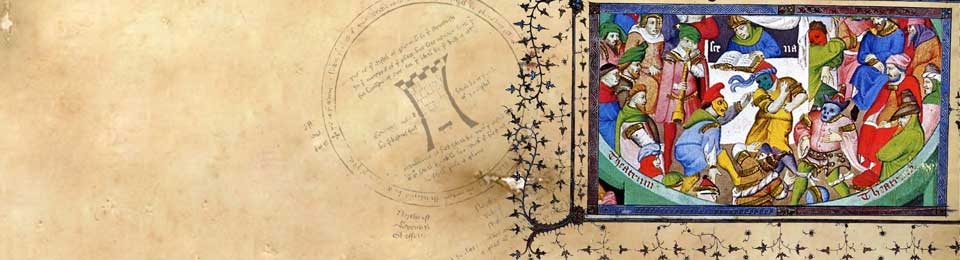

The image at the top of the page, incidentally, is Holbein’s depiction of a fool’s sermon to an audience of fools from Erasmus’ In Praise of Folly.

The “climax of the play” is a term that only entered drama criticism at the turn of the 19th/20th century. Pre-Shax. plays don’t have climaxes. They develop along the lines of formal rhetoric, as demonstrated by the Latin/Terence texts. This is a long play with a break for lunch/toilets. The second half ends with laughter when, one would think, the audience goes off for supper and talk about the performance.

That’s a very useful corrective, Joanne, and one I think that’s particularly hard for the ‘modern’ theatrical mind to understand.

Probably because such questions of form/genre don’t get much scholarly attention. But the “well made play” of the 20th century was already breaking up with the agit prop types even though “didactic” was a negative term. And the morality plays are certainly didactic and make little attempt at anything called realism. They’re talk, talk, talk, around a loose story/narrative. That’s where Shakespeare got his soliloquy practice, I imagine.

And that’s exactly the kind of 1980s political street theatre that Tam Dean Burn said this play reminded of when we were rehearsing in January.

Agit-prop sounds good to me! I’m enjoying all this talk from afar. Thank you all….