I thought it might be interesting to share some of the discussions the team have been having about the set and use of space in the forthcoming performances, as these are informing how we design the outdoor productions.

This first question concerns what sort of dramatic action can or cannot happen on the platea. The platea is an area of the stage in the medieval period, whose theatre often used locus and platea staing. The locus was an area which very much concerned the world of the play, a tree on the stage, for instance, by which characters would stand to show they were in the forest, or the sign of an inn, to demonstrate that characters were in a pub – these are all examples of loci. The platea, by contrast, is a threshold space which is neither fully immersed in the world of the play, nor outside of it and in the audience – it is somewhere from which characters may talk to the audience, but may also withdraw back into the play itself.

How and where we site the platea is especially important for A Satire of the Three Estates because of the sorts of questions we want to explore about political space and its accessibility/inaccessbility to the public or commonwealth. There are definitely transgressions of space in the play. The Pauper, for instance, is told be Diligence on his entry (1938-1941):

Where have we gotten this goodly companion?                               Â

Swyth out of the field, false raggit loon!                                   Â

God wait if here be ane weel kept place,                          Â

When sic ane vile beggar carl may get entries.

Here the Pauper is being told that he cannot even be among the audience in the field in which they stand But not only does he transgress Diligence’s command by getting up on the stage, in an intensely radical moment he even jumps up onto the King’s throne – an area that we may imagine is one of the play’s loci.

Moments such as this, and when John the Commonwealth jumps the ‘stank’ to enter the parliament, foreground the importance of who is and who isn’t allowed to inhabit the various parts of the stage in this play. A key question for the team has been whether the parliament staged in Part Two of the play should be conceived of as a loci or as part of the permeable space of the platea. Please see below for the research team’s debate about this and feel free to contribute your thoughts:

Can parliament happen on the platea?

Greg Walker – It could, perhaps. But the point of the play is surely that Parliament doesn’t really represent the people (and audience) until John and Pauper get in and John joins the estates with his gay garmoun at the end. If it was all happening in the platypus, then the visualisation of the idea that the audience is part of the excluded ‘people’, and parliament is happening somewhere else doing its business might get lost. We surely want to avoid the modern sense of parliament as a representative body of the people. The 16th century parliament is a gathering called by the prince to advise him. He chooses who comes, when and if it gathers, and when it is dismissed.

Tom Betteridge â when the three estates enter they come from the pavilion [Heir sall the Thrie Estaitis cum fra the palyeoun, gangand backwart, led be thair Vyces ] this suggests a sense in which entering Parliament is equivalent to entering the space of the play â I am assuming that âthe palyeounâ in this stage direction is the place from which the actors enter. In these terms I think Parliament could take place in the platea â it should not be in the field since that is where the people are but equally it should not be in the court since it has to be a space whose boundaries are up for debate or at least can be suspended / staged.

Greg Walker’s response – I suppose it is possible for the Parliament to take place in the platea, but it would have to be clear that this isn’t the same space where the tailor and sowter and their wives, and all the other representatives of the people do their thing. We’d have to have a separate acting space for them distinct from the parliament space.

Parliament is summoned by the king (or regent) to them, wherever they happen or want to be, so it would be more likely to happen in or around a palace or seat of government. We’d be making quite a statement about the accessibility and willingness to listen of the king at the end of part one if he came into the platea and summoned the estates to him there. Which might clash a bit with the notion that then Pauper and John have trouble getting in. But it could be done, I suppose…

Ellie Rycroft â As Greg has said, the Scottish parliament happens wherever the King is, whether this is a palace or the Tolbooth in Edinburgh. The Tolbooth was the most common venue so parliaments were not usually at the court. The platea in theatre history is the permeable space in which characters can address the audience but still be part of the play, so it is not somewhere where I think we would find the Estates or Rex as they donât do that sort of thing, but I agree with Tom that the permeable space has shifted to some degree into the âfieldâ. Might it be useful to think about the stage we propose to have in front of the semi-circular area of loci not as the platea at all but an extension of the locus, and imagine that there is a continuum from the definite audience interaction of the field, through the spaces we have set up towards the King? Or does this fudge the matter?

John McGavin – I think that the separation of the parliament from the people is important for the reasons Greg and Ellie suggest, but the connection with the people can be achieved on the awful parodic âridingâ to Parliament, and then the parliament is held in a location theatrically between the âcourtâ and the space into which people might go. John the Commonwealth has to cross that area so I agree with Gregâs final comment on divisions of theatrical space. I do also agree with Ellie and Tom that the meaning of space changes in relation to the nature of the action: it is John the Commonwealthâs having to cross a space that defines the separation of the parliament from the people.

Sarah Carpenter – is the âfencingâ of the parliament crucial here? Itâs a formal part of establishing the parliament (according to late records generally done by the Lyon King), and it seems to establish the parliament as a parliament wherever it is sitting. (Learneyâs article on parliamentary ceremonial quotes that the person fencing: âbiddis and defendis that ony man dystrobill this court wranguislyâ (134) see SHR 21, 61. And SHS Sheriff Bk of Fife, 406) That suggests that the parliament could sit anywhere, but that once itâs sat that place is formally established as a locus by the fencing?

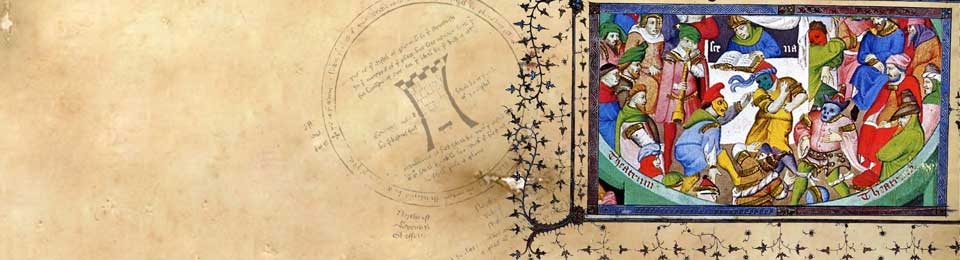

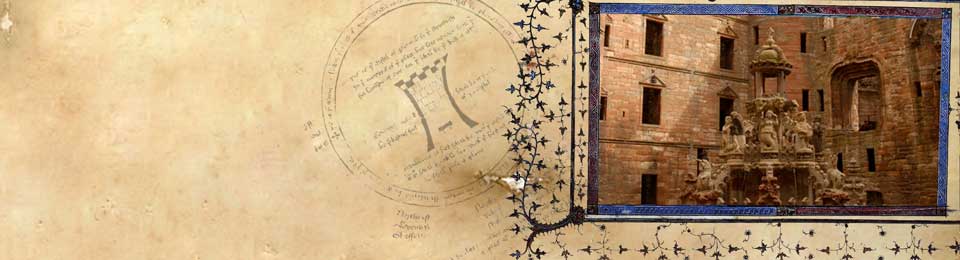

The picture I find useful is this one â even though itâs not Scottish, and is a council rather than a parliament. It does offer that sense of being visible to, but closed off from the âpeopleâ, which seems quite important: